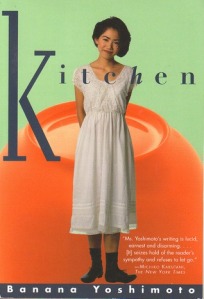

Two stories, “Kitchen” and “Moonlight Shadow,” told through the eyes of a pair of contemporary young Japanese women, deal with the themes of mothers, love, transsexuality, kitchens, and tragedy.

Review:

Banana Yoshimoto likes circles: opposing ideas and feelings that turn round and round until you’re so dizzy that finally you can see clearly, the opposites collapse into each other, and you see they are the same. Melancholy and hope fuse together; pain accompanies joy; love is both the origin of and cure for loneliness. Around and around these feelings go, the only certainty being, of course, how difficult this oscillation makes life, leaving us with no choice but to, as one character says in Kitchen, “adopt a sort of muddled cheerfulness.”

There are two stories in this book: the titular Kitchen, about a man and woman who both find themselves orphaned in their early 20s, and Moonlight Shadow, about a woman, again in her early 20s, whose boyfriend dies suddenly. Thus even the collection works in a melodious, circular format. These are distinct works but they blend well together, enhancing each other’s gloominess more and more until it soars with sorrow.

Yoshimoto understands how alluring sadness can be. It is intoxicating and safe. Labyrinthine, with deep holes to get lost in. The allure of sadness is why I read and enjoyed her book. Sadness sharpens: abstract ideas narrow to single points, thoughts become clearer. But Yoshimoto also understands that after a certain moment sadness dulls and blurs. Which is why she allows her beleaguered characters to wallow in their pain but also eventually forces them to find an exit from it.

In both stories love is both question and answer, root and flower, cause and effect. The characters find sadness because of love and finally find happiness because of it too. Yoshimoto has an eye for that perfect moment, the nadir/zenith of sadness before it spins round the circle to joy. In Kitchen that moment is a romantic gesture worthy of a John Hughes film. Moonlight Shadow’s climax would be downright maudlin penned by most authors, but Yoshimoto manages to make it poignant without being cloying.

Really, Yoshimoto isn’t saying anything terribly original. She says that we must let go of lost loves or we stand to lose ourselves. But she says it with just the right amount of melancholy, just the right amount of hope: in short, she says it in a way that I imagine actually feels like letting go.