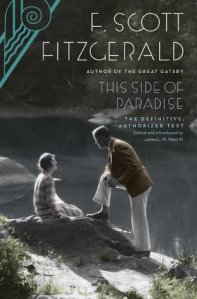

This Side of Paradise, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s romantic and witty first novel, was written when the author was only twenty-three years old. This semiautobiographical story of the handsome, indulged, and idealistic Princeton student Amory Blaine received critical raves and catapulted Fitzgerald to instant fame. Now, readers can enjoy the newly edited, authorized version of this early classic of the Jazz Age, based on Fitzgerald’s original manuscript. In this definitive text, This Side of Paradise captures the rhythms and romance of Fitzgerald’s youth and offers a poignant portrait of the “Lost Generation.”

Review:

The literary landscape is overpopulated with insufferable egotists, often of the white male semi-autobiographical variety, but what separates the sympathetic from the antipathetic?

This Side of Paradise is F. Scott Fitzgerald playing in his usual time period with his usual beautiful words. In the booming era leading up to and following the Great War, men were being lost and found. A lucky guess on the stock market made you a millionaire and gave you a name, but battles in Europe led to a battered generation of men questioning where they were going and if it was anywhere good. Amory Blaine spends the entirety of This Side of Paradise as one of the lost until he miraculously finds himself at the end.

This joyous climax did not evoke any triumphant readerly emotions here, however, because Amory Blaine is the most hateful, undeserving character I’ve ever met. And sure, perhaps his character is a window into the minds of the Lost Generation, but if people were/are thinking like this, then I don’t want to know about it. Amory meanders through life, striving towards something indefinable, which is to say striving towards nothing. His privileged childhood and adolescence lead him to Princeton and into the arms of many delightful debutantes whose chief qualities are soft lips and the proclivity to use said lips even before a marriage proposal. Amory’s striving often looks more like stomping. In climbing upwards, he crushes these women and various other members of the underclass (in other words, anyone who didn’t spend his sixteenth and seventeenth years “prepping” in Connecticut, New York, or Massachusetts), an ascent which again, isn’t upwards, but nowards, since he has no destination except superiority.

These are legitimate words uttered by/about Amory:

Oh it isn’t that I mind the glittering caste system. I like having a bunch of hot cats on top, but gosh, I’ve got to be one of them…But I hate to get anywhere by working for it.

Amory usually liked men individually, yet feared them in crowds unless the crowd was around him.

He took a sombre satisfaction in thinking that perhaps all along she had been nothing except what he had read into her ; that this was her high point, that no one else would ever make her think.

And say all you will about unlikeable narrators—I’m certainly an ardent defender as seen here—but something about Fitzgerald’s depiction of Amory rings false. I didn’t know if I should pity him or sympathize with him, so I ended up being disgusted by him. Amory, like personages from The Great Gatsby, is a careless man. But his thoughtfulness is supposed to make him a redeemable man as well, so that we cheer when he reaches epiphanous clarity riding along the New Jersey highway in the novel’s final pages.

Yet I couldn’t cheer for Amory, I couldn’t like Amory, I couldn’t even tolerate reading his various anodyne thoughts. Insipidness is still insipidness, even if it dresses well, prepped at St. Regis, studied at Princeton, and finds itself described by the magic words of F. Scott Fitzgerald.