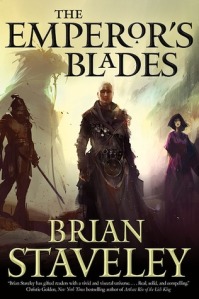

When the emperor of Annur is murdered, his children must fight to uncover the conspiracy—and the ancient enemy—that effected his death.

Kaden, the heir apparent, was for eight years sequestered in a remote mountain monastery, where he learned the inscrutable discipline of monks devoted to the Blank God. Their rituals hold the key to an ancient power which Kaden must master before it’s too late. When an imperial delegation arrives to usher him back to the capital for his coronation, he has learned just enough to realize that they are not what they seem—and enough, perhaps, to successfully fight back.

Meanwhile, in the capital, his sister Adare, master politician and Minister of Finance, struggles against the religious conspiracy that seems to be responsible for the emperor’s murder. Amid murky politics, she’s determined to have justice—but she may be condemning the wrong man.

Their brother Valyn is struggling to stay alive. He knew his training to join the Kettral— deadly warriors who fly massive birds into battle—would be arduous. But after a number of strange apparent accidents, and the last desperate warning of a dying guard, he’s convinced his father’s murderers are trying to kill him, and then his brother. He must escape north to warn Kaden—if he can first survive the brutal final test of the Kettral.

Review:

Here is a (not really) spoiler summary for the first 75% of The Emperor’s Blades: An emperor, dead; a plot to kill his three children, underway; breakneck action to match those high-stakes…completely missing.

We start the book with the death of an emperor—as auspicious a premise as there ever was—but until the final quarter, nothing of importance happens. It’s quite shocking actually: a book that is going to be published could stand to lose its first 300 pages. All that happens in those 300 pages is an extended montage scene. The two princes—one training to be an elite soldier, the other serving as a monastic acolyte—get into various unimportant scrapes that are described in painstaking detail. (Literally ‘painstaking’: the pain of these unnecessary details is comparable to the pain of impalement by a stake.) Now I can never resist a good montage scene. Upbeat music coupled with characters getting ready to chase their goals is a perfect combination. But after a while I was hoping for, then praying for, then sacrificing cows at a homemade altar for a conflict to maybe kinda sorta sometime soon appear. Please Zeus?

As I waited very patiently, I was subjected to simplistic and forced dialogue that merely served to push the plot along. I also had to suffer dumb characters. Get ready to scoff and eyeroll when a character neglects to notice a big fat whopping clue slapping him on the side of his face! It happens quite a lot, especially with soldier prince. It’s even worse because the story is so emotionally simplistic, it is impossible to connect with the characters.

But what bothered me most about this novel was its treatment of female characters. Now this rant does not entirely belong to The Emperor’s Blades. Rather it is the result of hundreds of fantasy books, normally written by male authors, committing the same error. There are three POV characters in this novel, but I’ve only mentioned the two princes. That’s because the princess’s chapters are very few. What’s worse, in each of her chapters we are constantly reminded that this girl cannot be emperor, that she has no role in this man’s fantasy world. I don’t like “strong” female characters who are constantly told that they’re a rarity, that sexism does not want them where they currently have fought to be. Because honestly this just reinforces the idea that it is unnatural for women to be in positions of power. It suggests, quite unconsciously but regardless, that ambitious and successful women are an aberration. Give me a fantasy novel where men and women are equal and absolutely nothing has to be said about it because it’s normal!

Despite all these gripes, The Emperor’s Blades is a mildly entertaining novel that will be appreciated by those who like their fantasy more popcorny and less meaty. Do know that this is a series beginner and there is absolutely zero resolution here. Will I be back for book two? Possibly, since the mythology of this world seems interesting and I didn’t learn enough about it for my taste (instead I was treated to another knife fight or something). But I’m going to read reviews carefully before coming back for more to make sure that all of the significant action isn’t stuffed into the final 100 pages.