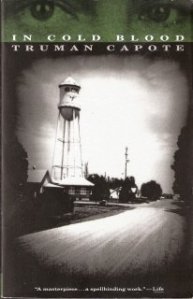

On November 15, 1959, in the small town of Holcomb, Kansas, four members of the Clutter family were savagely murdered by blasts from a shotgun held a few inches from their faces. There was no apparent motive for the crime, and there were almost no clues.

As Truman Capote reconstructs the murder and the investigation that led to the capture, trial, and execution of the killers, he generates both mesmerizing suspense and astonishing empathy. In Cold Blood is a work that transcends its moment, yielding poignant insights into the nature of American violence.

Review:

“I didn’t want to harm the man. I thought he was a very nice gentleman. Soft-spoken. I thought so right up to the moment I cut his throat.”

How can two opposite things both be true? How can someone be a killer but not—never—be worthy of being killed himself? How can the world treat you poorly but in doing so not give you the right to treat it poorly?

The answer to these hows? A set of arbitrary human laws that we have tried to bend around the unarbitrary universe.

Murder, as a subject of debate, doesn’t seem particularly sticky. And yet we have hundreds of thousands of pages of judicial literature devoted to its consequences and hundreds of thousands of pages of fiction and non-fiction literature dedicated to its perpetrators, its victims, its sufferers, and its enforcers. The rule humans have developed for murder is as simple as the one recorded in the Bible a few millennia ago, “Thou shalt not kill,” and yet…we kill. And yet, we struggle to understand why.

The murder here is both as unfathomable and fathomable as they all are. Two greedy men stomped on by the world decide to rob a prosperous Kansas farm family for money. Failing to find a massive safe full of cash, they abandon the enterprise but still decide to brutally murder the four family members.

In Cold Blood is widely considered the exemplary work of the True Crime genre. Never before has a family’s doom been quite so picturesque. It is the most fantastic of murders, more atavistic than the “original” murder of Abel by Cain. The dead family is the family, more good, wholesome, and kind than it should be possible to be. And the killers are the killers, not entirely psychopathic but not entirely rational. They’re straight-up thugs, beat-up and blackhearted, motivated by a special blend of vindictiveness and simple desire.

What makes it even more fantastic is its hyper-realness. Verisimilitude cannot substitute for newspaper clippings, wet pools of blood, and the itch of a real rope around a real man’s neck. This all happened, Capote reminds us with every tragic detail. A family met death while the family in the neighboring farmhouse slept through the night. You can google “Perry Smith” and stare into his drooping eyes, just as the Clutter family might have stared into those eyes, tied up, desperate, wondering but probably more so knowing that they’d be the last thing they’d see. Likewise you can google “Nancy Clutter” and see her brilliantly coiffed hair paired with a genuine smile.

While the Clutters were killed, so were the perpetrators, just later and in a different way. And looking at all their faces—their real faces—it’s easy to forget those human laws and it’s hard to say whom you pity more.